A Brief History of Taiwan - the Island That Became Everyone's Problem

From backwater to powder keg, Taiwan has changed like nowhere on Earth in the past century.

We talk a lot about Taiwan these days. It’s often said that if World War III begins, it will begin in Taiwan, one of the world’s most fragile geopolitical and economic fracture points. Yet for all the headlines, few people outside East Asia have a clear sense of what Taiwan actually is, or how it came to be. Most in the West, frankly, would struggle to find it on a map.

I had the good luck to spend 3 months in Taiwan this year, and I found a country that was beautiful, friendly, surprising, and somehow felt like the safest place I’ve ever been, despite the political situation from afar.

I’m excited to talk about life in Taiwan, about its food, streets, architecture, people and nature — but before I get to all of that, I want to start with history. You never really understand a country until you know its history, and nowhere is that truer than in Taiwan. This article began as an intro for an essay about modern life in Taiwan, but ended up taking on a life of its own. Here’s the story of how Taiwan came to be the state it is now.

Taiwan lies off the coast of China, yet for most of its history had very little to do with its big neighbour. In fact, there is no confirmed contact between the two at all until ~1300 AD.

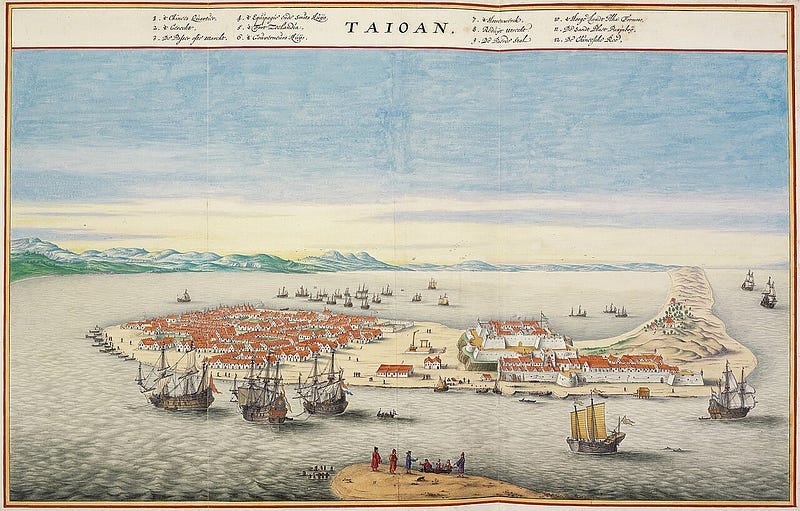

Mostly populated by indigenous people (who are believed to be the ancestors of the Polynesians that stretch from the Philippines to Hawaii today), the first formal occupation of Taiwan was actually by the Dutch, who counted fewer than 2,000 Chinese on the island when they arrived in the 17th century; these were mostly from Fujian, the closest Chinese province, and many only came seasonally for industries like fishing. Most of that Chinese population was wiped out by brutal conditions as slave labourers for a Dutch fort.

The Dutch welcomed young male migrants from mainland China, with the population swelling to tens of thousands by the time they were driven out of Taiwan. For the next 200 years, Taiwan would remain a tributary state of the Qing Dynasty. This period saw continuing migration from Fujian, but a combination of ferocious storms, tropical disease and seemingly endless revolts and rebellions ensured that the Chinese state had little real control of the island.

This all changed in 1895, when a newly industrialised Japan shocked the world by easily defeating China in a war (up to that point, the Japanese had traditionally been referred to as “dwarf pirates” in China). Taiwan became Japan’s first great colonial experiment, and developed with astonishing speed. The 50 years (1895–1945) of Japanese colonisation saw the building of Taiwan’s first public schools, highways, banks and ports, turning it from a disease-ridden and opium-addicted backwater to a modern industrial economy. As a result, Taiwanese today still tend to think fondly of the Japanese Empire, in sharp contrast to most of Asia.

The modern phase of Taiwanese history began shortly after World War II, when Mao Zedong’s Communists seized power in China. China’s Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party moved to Taiwan with over 1 million refugees and the national art, gold, silver and dollar collections, preparing to regroup and counterattack. Until the 1970s, Taiwan (continuing to call itself the Republic of China) expected to invade the mainland and described itself as the rightful government of mainland China. In fact, Taiwan held China’s seat on the UN Security Council until 1971.

Things changed with Nixon’s visit to China and the Chinese economic boom. It became clear that Taiwan would never be able to conquer the mainland, and although Taiwan is still officially called the Republic of China, most Taiwanese today just want the island to be left in peace and prosperity — of which there is plenty. Taiwan began a manufacturing boom of its own decades ago (when I mentioned the country to my parents, their first reaction was “Oh, the country that made all the toys”).

It has made great strides since: Taiwan transitioned from military dictatorship to true democracy in the 1990s, and also emerged as the world’s dominant producer of semiconductors in the 2010s. Today, Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer TSMC is often described as the world’s most important company; in Taiwan, it is sometimes called the “Sacred Mountain” of national defence.

If you know anything about Taiwan, you know about its dispute with China. Taiwan is, for all purposes, an independent nation; ethnically Chinese, but just as different as Singapore, for example. China, on the other hand, claims that Taiwan is nothing more than a renegade province and wants to “merge” with it, possibly through blockade or even invasion, for several reasons.

Firstly, Taiwan’s very existence is a threat to the Chinese Communist Party. As a rich, free, democratic nation, it is a living rebuke to China’s claim that “traditional Confucian values” are incompatible with Western-style democracy. Should the CCP get credit for making China rich when Taiwan, basically China without the CCP, is even richer?

Secondly, Taiwan is viewed as an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” of the US, a vital strategic chokepoint and base for NATO operations in the Asia-Pacific.

Thirdly, Taiwan’s separation from China is seen as an extension of the “Century of Humiliation”, when foreign powers repeatedly trampled over China with impunity. Taiwan’s independence, like that of Hong Kong, is a daily reminder of China’s weakness, of an era when China went from the world’s leading state to a helpless and impoverished backwater.

Xi Jinping has ordered the Chinese military to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027, and you’re rarely more than a few metres from an air raid shelter in Taipei, but people in Taiwan are generally skeptical of an imminent Chinese invasion. They’ve heard the warnings their whole lives, and Chinese threats now sound a little “boy who cried wolf”.

I hope, for the sake of an island I loved a lot, that they’re right.