When my European, Asian, and Latin American friends ask me which foods Ireland does best, I like to point out that you’ll find Chinese, Italian and Mexican restaurants across the world, but never an Irish one. There’s a reason for that: we’re no culinary powerhouse.

But occasionally, someone will reply that Irish pubs can be found everywhere, which is true. Ireland does alcohol well. Besides being a whiskey powerhouse, we produce beloved and delicious drinks like Guinness and Bailey’s. We’re known to enjoy a pint or five, and for being generally good fun.

But none of that explains the sheer ubiquity of Irish pubs. Why is it that from Mount Everest to Argentina, from Uganda to Taiwan, you can find Irish bars but not necessarily Czech, Spanish, English or Japanese ones?

I’ll start with an explanation of this curious phenomenon, and then give my opinion on it. How authentic is the average Irish bar? Does the Guinness really taste better back in the Old Country? And is it a good thing that we’ve become the McDonald's of the global pub trade?

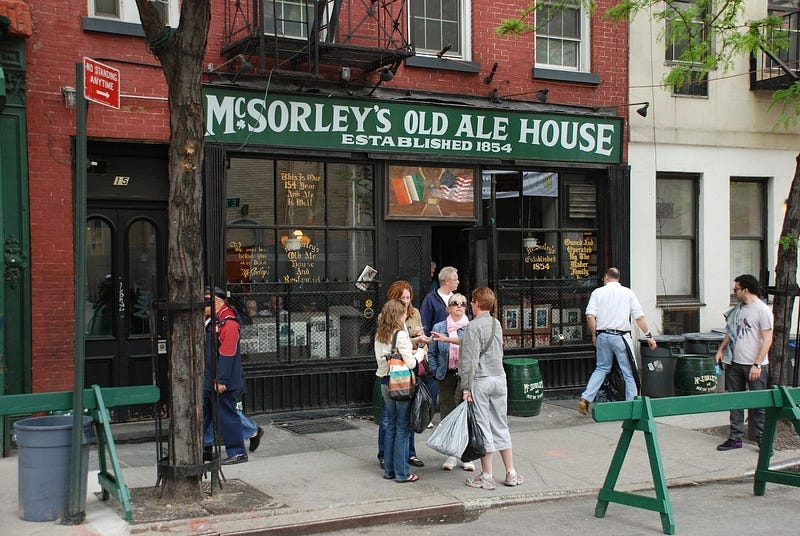

The story starts in the 1970s. Irish bars made their way abroad much earlier than this, of course — the famines and rebellions of the 19th century in particular pushed millions of Irish to places like the Northeastern US, Britain and Australia. Yet Irish pubs were certainly not “trendy”; these pubs, rather than being a marketing gimmick, largely served members of the diaspora, and dropped the Irish branding as the Irish migrants assimilated into the mainstream culture of wherever they went.

So, back to the 70s. Late in the decade, an architecture student in Dublin called Mel McNally persuaded his dubious professors to let him do a project on local pubs. He visited hundreds of pubs across the island, analysing what they had in common and how they differed, as well as what the most successful ones did well.

A little later, in the late 80s, Guinness did lots of market research into their global sales and noted the remarkable improvement in sales wherever an Irish pub was founded — not just sales from the pub itself selling Guinness, but also from rival local bars adding a Guinness tap to stave off the competition.

Perhaps in time, Guinness might have tried to establish a Wetherspoons-style franchise, but a more attractive idea appeared when Mel McNally founded a design agency called the Irish Pub Company in 1990. McNally wasn’t going to own any pubs himself — this was going to be an export business. The IPC would offer a range of different pub styles to choose from, adapt the chosen style to the space available, and then have teams of carpenters, painters, glass-makers and other craftsmen in Ireland build the tables, chairs, bar counters, mirrors and ornaments needed for an “authentic” Irish bar. This would be packed into a storage container, spend a few weeks at sea, and then be assembled into an “Irish pub” upon arrival.

Part of the genius of the idea, and what attracted Guinness, was the concept of building “a franchise without a name”. The visually distinctive and craftmanship-heavy nature of Irish pubs (as opposed to Italian espresso bars, for example) enabled a thriving business without any need for centralised corporate ownership. With Guinness’ financial backing and networks, the IPC creates the bar’s aesthetic, delivers workshops, and supplies a business plan and loans; the pub owner gets to choose the pub’s name.

Everybody wins. Guinness has seen explosive growth in international sales; the IPC employs hundreds of Irish craftsmen; and the pub owner knows he is quite unlikely to go out of business, and might have an easier time starting in the first place — no bank in their fight mind would offer a loan to open an Irish bar in Siberia, but the IPC has.

The Irish mail-order pub game is going so well that IPC now has competitors like ÓL Irish Pubs and Ballance Hospitality. Today, thousands of Irish pubs around the globe can trace their origin to Irish McPub agencies like these (over 2,000 by IPC alone), and thousands more have been started independently at a fraction of the price now that Irish pubs have been a globally recognisable brand.

After 5 years of pretty much full-time traveling, I’ve been to a fair number of Irish pubs. Most have been pretty inauthentic, and probably more have been English-owned than Irish-owned. Not to shit on our much-beloved neighbours, but I’m still a little bitter over all the Irish customers being kicked out of an “Irish pub” in Koh Phi Phi, Thailand, during the 2018 Football World Cup (Croatia beat England in the semi-final; naturally, the Irish wore Croatian jersey and celebrated enthusiastically when England lost, much to the annoyance of the sullen English manager and crowd).

I also remember going to an Irish pub in Budapest to watch an All-Ireland Hurling Final (an event similar to the Super Bowl within the world of Irish sport), and the Australian owner agreeing only once a minor golf or cricket game was over. Never has the homeland felt more distant. I can also say that any Irish bar with “Irish car bombs” on the menu is likely to be met with raised eyebrows.

But then, inauthentic doesn’t mean “bad.” I remember one Irish pub in Palermo which I rarely went to because the prices were too high (probably the most authentically Irish thing about it), but which a couple of East African friends raved about because of the chicken wings, which were apparently the best they’d ever eaten in Europe. Chicken wings are certainly not an authentic Irish food, but who cares if they taste good?

More broadly, Irish bars tend to be pretty social and full of people who speak English, which is useful if you’re somewhere where you don’t speak the local language. If you’re somewhere like Japan or Thailand where local bars often refuse foreigners, you usually won’t have to worry about that treatment with an Irish bar.

Irish bars are usually more expensive than local spots but will rarely have minimum orders, table fees, mandatory tips or service charges, traditions like otoshi, or toilets that even customers must pay to use. They often have a better selection of bar games (darts, pool) and social activities (live music, comedy nights, pub quizzes) than the average local bar does; they also tend to have a wide range of premium international lager and draft beers (not very Irish), and of course our beloved Guinness.

And even in Ireland, we all have a different sense of what makes an “authentic” Irish bar. For me, the hallmark of a good Irish pub is a roaring fireplace and a night or two of Irish traditional music during the week, which are virtually impossible to find abroad. But then, I’m from the countryside (where fireplaces are more common than in city bars), and I mostly spend a couple of months in Ireland each year around Christmas and New Year, which helps explain the preference.

There are other kinds of Irish pubs. The 6 styles offered by the IPC include the country pub style but also Victorian (lots of brass and mirrors) and Spirit Grocer (a style that emerged during Ireland’s 19th-century temperance movement, when declining alcohol sales forced pubs to double as grocery stores to stay afloat). Mel McNally reckons that the best ones have stained glass windows, a bar that can be seen from any point in the building, and snugs (booths) for small group socialising.

I’ve been to a few IPC-designed pubs before, and they can look exactly like the real deal since they basically are Irish-made and designed, if sometimes not really “worn” enough to feel cosy. The staff may well be Irish in places with big overseas Irish communities (Australia, Canada, New York), and a large Irish clientele also makes sure the Guinness flows regularly and isn’t left to sit in the pipes for hours, which is the main reason it tastes better in Ireland than abroad.

I think many people would be surprised to know that their beloved, authentic local Irish pub is basically an IKEA-style flatpack affair, but I suppose it doesn’t make my life any worse, and it’s a better thing to be known for internationally than famine or terrorism. I wish some places leaned less into the leprechaun imagery, and that places keeping real Irish artisans in work made a bigger deal of it; I wish Irish bars weren’t always the most expensive bars on the street. That said, you can’t have everything in this world.